-

Posts

7,282 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

2,416

Content Type

Forums

Blogs

Events

Resources

Downloads

Gallery

Store

Everything posted by allheart55 Cindy E

-

Cybercriminals are spreading malware via torrent distribution networks, using an automated tool to disguise the downloads as trending audio, video and other digital content in an attempt to infect more unsuspecting victims. Researchers at InfoArmor say they have uncovered a malicious torrent distribution network that relies on a tool called RAUM to infect computers with malware. The network begins with a torrent parser, which collects information about some of the most popular torrent files circulating around the web. Computer criminals then apply their RAUM tool to create a series of malicious files. Some are fake copies of those popular torrent files that in reality hide notorious malware such as CryptXXX, Cerber, or Dridex. Others are weaponized torrent files, while others still are parsed torrent files that rely on a high download rating, a reputation which the attackers artificially inflate by abusing compromised users' accounts to set up new seeds. Like many attack campaigns in the underground web, the RAUM network operates according to an affiliate system. InfoArmor explains: "The so-called 'RAUM' tool has been actively used on uncovered underground affiliate networks based on a 'Pay-Per-Install' model (PPI). This model leverages paying cybercriminals to distribute malware through modified torrent files that are joined with malware." That type of framework allows the network's administrators to carefully screen its members. In fact, no one is allowed to join without receiving an invitation from another pre-approved member. Together, all of those malicious files provided by affiliates form the basis of the network's seedbase, which admins manage using an easy-to-use dashboard. Criminals monitor those files intently to see if anti-virus solutions have flagged any of them as suspicious. To protect against detection, some of the files are hosted on the Tor network. All that remains is distribution. Initially, computer criminals relied on uTorrent, but now they're using virtual servers comprised of hacked devices to get the job done. This complex infrastructure has helped the computer criminals meet with quite a bit of success over the past few months, InfoArmor notes: "According to expert statistics, malicious torrents infect over 12 million users a month, creating significant security risks for users on a myriad of platforms. In many instances, popular ransomware such as CryptXXX, CTB-Locker and Cerber, online-banking Trojan Dridex, password stealing spyware Pony, and others were associated with the identified RAUM instances. We have identified in excess of 1,639,000 records collected in the past few months from the infected victims with various credentials to online-services, gaming, social media, corporate resources and exfiltrated data from the uncovered network." To protect themselves against this campaign, users can reference the indicators of compromise included in InfoArmor's blog post It's always a good idea to maintain an up-to-date anti-virus solution on computers and follow sensible precautions to avoid exposing their computers to malicious torrent files. Source: Graham Cluley

-

- cybercriminals

- malware

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

Can you imagine just how much online criminals would pay to be able to hijack, and even delete, any page on Facebook? Facebook pages are used by organizations, businesses and high profile figures like FC Barcelona (94 million fans), Vin Diesel (100 million fans), and Shakira (104 million fans) to promote their brands and are an essential part of their marketing. Hey, even Bitdefender has a thriving Facebook page, where we keep over one million fans (and counting!) up-to-date on the latest security threats and share advice on how to keep your computer safe online. For a celebrity or well-known brand to lose control of its Facebook page could be catastrophic, eroding the trust of fans and – potentially – spreading malicious links or hate speech. It’s easy to picture how a hacker could demonstrate their power to break into a particular Facebook page, and then attempt to extort money from the page’s legitimate owner by making threats of doing it again in a more malicious way next time. My guess is that if someone were able to devise a way of hacking any page on Facebook, that criminal gangs would be prepared to pay a pretty penny for the method. Chances are that a hacking gang would pay more than the $16,000 Facebook has just paid a security researcher who uncovered a method to takeover any Facebook page in less than 10 seconds. Arun Sureshkumar responsibly disclosed the vulnerability to Facebook’s security team at the end of August, and will share further details of the flaw at the 0SecCon being held in India later this month. As Sureshkumar demonstrates in a proof-of-concept he made of the exploit, an insecure direct object reference vulnerability allowed him to bypass authorization checks in Facebook Business Manager – the free feature which allows multiple members of a team to share access to a Facebook page without having to share login details. The video – best viewed in full screen mode – sees Sureshkumar change a business ID number in a web request to that of the ID number of the page he wants to hack, granting him the required rights to surreptitiously add himself as a manager of the targeted Facebook page. Clearly Facebook should have done a better job at checking whether the request was authorised, rather than just saying “Oh, I’ll trust that parameter I’ve been passed as genuine”. In his blog post, Sureshkumar explains that he could have taken over the pages of famous figures such as Bill Gates and Barack Obama, and performed critical actions such as page deletion. For its part, Facebook’s security team appears to have patched the vulnerability rapidly – and decided to reward Sureshkumar through its bug bounty program: “I wanted to reach out and inform you that we have decided to pay you a bounty of 16,000 dollars for this report. A majority of the bounty is for the page takeover capability of your exploit, but while investigating your report we discovered and fixed another issue as well, so the bounty is a little higher because of that. You can expect the standard longer payout message later in the week.” Well done to Facebook for fixing the problem, Sureshkumar for finding it in the first place and for his responsible disclosure. But I can’t help but feel that this vulnerability would have been worth much more than $16,000 on the criminal underground – and that Facebook might want to assess its bounty rewards in future to ensure that vulnerability researchers are properly rewarded, and not tempted by the dark side… Source: hot for security

-

-

Remember how, earlier this summer, a hacker claimed be selling, credentials for at least 200 million Yahoo accounts? Well, unfortunately for hundreds of millions of Yahoo users, and the company itself, the hack appears to be legitimate — and bad. Tech site Recode reports this morning that Yahoo is expected to confirm the massive data breach this week. Sources “close to the situation” did not confirm to Recode the exact extent of the breach, other than to say it is indeed hundreds of millions of user accounts. Those sources noted to Recode that the breach is indeed widespread and serious, and likely to result in government investigations and legal actions. About the 200 million estimate, one source told Recode, “It’s as bad as that. Worse, really,” which is not good news for anyone, but is especially bad for Verizon, which is in the midst of acquiring Yahoo in a $4.8 billion transaction. As Recode points out, the sheer scale of the breach is staggering, and the legal liabilities that could result from it are equally huge. In short, shareholders may well freak out. Yahoo did not return Recode’s request for comment, perhaps unsurprisingly. Yahoo is expected to confirm massive data breach, impacting hundreds of millions of users [Recode]

-

- data breach

- hacker

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Unexpectedly received a USB stick in the post? Whatever you do … DON’T PLUG IT IN!! Police in the Australian state of Victoria are warning the public about cybercriminals’ latest tactic: randomly dropping unmarked USB sticks containing malware through letterboxes. The criminals are of course hoping that the unsuspecting recipients will plug the freebie USB drives into their computers. The state police’s online news warns: Upon inserting the USB drives into their computers victims have experienced fraudulent media streaming service offers, as well as other serious issues. Police are urging anyone with information about the people behind the scam to contact Crime Stoppers. Picking up and plugging in The criminals behind the USB drop are tapping into our curious, well documented and inexplicable urge to plug in any old USB stick we find lying around. Back in April, we reported about how vulnerable we are to malware shared through these abundant and inconspicuous devices. Surprisingly: …almost half of dropped USB sticks will get plugged in. A study published by a group of researchers from the University of Illinois, the University of Michigan and Google confirmed that many people would not only pick up and plug in a USB stick of unknown origin, but would also open files, click on unfamiliar links and send messages to email addresses they found on them. USB sticks have long been a means for distributing malware. Nearly five years ago we studied 50 lost USB sticks and found them riddled with viruses; 66% of them were infected with malware. Not just the public But it’s not just the public that is vulnerable to these types of scams. In 2011 the Western Australian Auditor General carried out a security exercise in which it left USB sticks in public places. The sticks had software on them that phoned home when used. Eight of fifteen government agencies involved failed the test, with agency staff connecting the USB sticks to their computers, allowing the devices to access their agency’s network. If you find yourself the unexpected recipient of a mystery USB stick, break it so that nobody else can plug it in and then put it into the bin. If you use USB sticks yourself then make sure you encrypt your data so you aren’t the victim of somebody else’s curiosity if you lose it. Source: Sophos

-

- letterboxes

- malware

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

Since shortly after the expiration of the year long free upgrade offer from Windows 7/8.1 to Windows 10 users on those operating systems stopped getting the prompts to take advantage of the upgrade. Microsoft stated at that time an update would be released to remove all of the Get Windows 10 updates from the systems of Windows 7 and 8.1 users who stayed put and opted not to upgrade to Windows 10. Well today is that day when all that now unnecessary software will be removed from those users systems through an update released today by Microsoft under Knowledge Base Article KB3184143. That update, which is entitled Remove software related to the Windows 10 free upgrade offer, removes the Get Windows 10 app and all associated software including these related updates: KB 3035583 -- Update installs Get Windows 10 app in Windows 8.1 and Windows 7 SP1 KB 3064683 -- Windows 8.1 OOBE modifications to reserve Windows 10 KB 3072318 -- Update for Windows 8.1 OOBE to upgrade to Windows 10 KB 3090045 -- Windows Update for reserved devices in Windows 8.1 or Windows 7 SP1 KB 3123862 -- Updated capabilities to upgrade Windows 8.1 and Windows 7 KB 3173040 -- Windows 8.1 and Windows 7 SP1 end of free upgrade offer notification KB 3146449 -- Updated Internet Explorer 11 capabilities to upgrade Windows 8.1 and Windows 7 After KB3184143 is applied your Windows 7 and 8.1 system will be clear of any and all Windows 10 related free upgrade software. Source: winsupersite

-

- expiration

- prompts

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Verizon told this woman that she had done over 400 searches on Amazon in a couple of days. She hadn't been on Amazon at all. She did, however, have a new Amazon app. Hmmmmm.......

- 2 replies

-

- data allotment

- overages

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

A piece of software masquerading as a security product from Malwarebytes is making its rounds on the web and distributing ransomware to unsuspecting users. This technique isn't new. Malicious software has been disguising itself as anti-virus solutions since the 1990s. What's significant about this particular attack campaign is the crypto-malware behind the mask: DetoxCrypto. The ransomware has been making quite a stir since researchers first detected it back in August. Already it has two variants to its name: a "Calipso" iteration that takes a screenshot of the victim's computer, and a Pokémon GO-themed encrypter. (To be fair, the latter isn't the only one of its kind.) Source: Bleeping Computer. But recent developments suggest DetoxCrypto might just be getting started. Christopher Boyd, a security researcher at Malwarebytes, explains the ransomware could be planning something big for the near future: "What we’re seeing at the moment is what appears to be a kind of trial run for ransomware distribution. There’s a couple of Detox Ransomware files doing the rounds, and though they’re all broken in terms of functionality and / or download / dropper URLs, it’s still a possible sign of things shortly coming around the corner and worth giving a heads up on." That being said, there's not much for users to worry about for the immediate future. Take a look at this image taken from the ransomware's VirusTotal page: See anything wrong with that entry? Last time I checked, Malwarebytes isn't spelled "Malwerbyte." That should automatically raise a red flag that this product is a fake. Not only that, but all current versions of "Malwerbyte" that Malwarebytes' researchers have come across do not encrypt a victim's files, which means they don't need to worry about data loss from this ransomware just yet. But things are fluid in the world of ransomware. You never know when a malware developer will plug a vulnerability or fix a spelling error in their product. With that being said, if you are looking to install anti-virus solutions like one of Malwarebytes products, make sure you do so from the vendor's real website directly. That way you don't have to worry about any of these middle men potentially pushing malware onto your computer. Source: Graham Cluley

- 1 reply

-

- 3

-

-

- malwarebytes

- ransomware

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

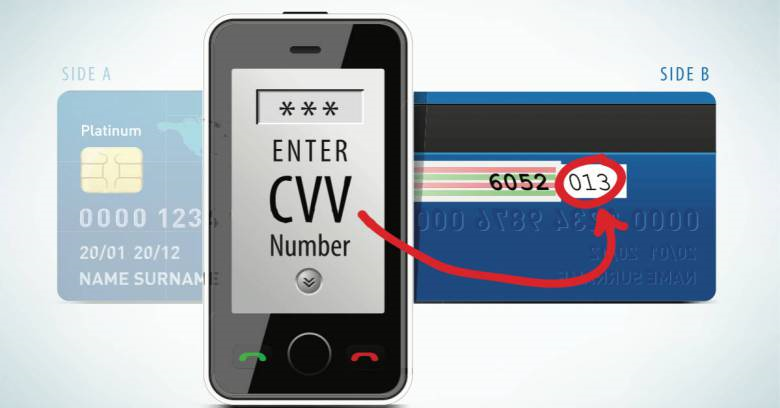

About two months ago, a Twitterer going by 0x2Taylor announced a sizeable data dump. More than 300,000 credit card records were uploaded to the file sharing service Mega; the data has since been removed from Mega, but not before it was widely downloaded by many interested parties. By some standards, 300,000 stolen records doesn’t sound very many these days. That’s a sad state of affairs, of course, caused by the daunting size of some high-profile attacks that have hit the news recently. This year alone, we’ve reported on breaches covering about three orders of magnitude, where each breach is in the exponential vicinity of ten times bigger than the one before it in the list: Opera announces data breach: stored passwords stolen for 1.7M users. Data breach in China: 100 million records used to hack 20 million Taobao users. 117 million LinkedIn records up for sale on the dark web. MySpace breach could be the biggest ever – half a BILLION passwords! Nevertheless, this newly-announced breach, dumped in a file by the name Bluesnap_324K_Payments.txt, is intriguing for two reasons. Firstly, the source of the breach – the company from which the data was stolen – hasn’t been determined. Secondly, even though the breach doesn’t include full credit card numbers (the so-called “long number” on the front of your card, usually 16 digits), it does include CVVs. Understanding the CVV CVV is short for Card Verification Value, confusingly also known as a CVC, where the second C means Code, and as a CVV2, where the 2 means it’s a “version two” CVV code, not that it’s the second such number on your card. On most cards, the CVV is a three-digit number printed, rather than embossed, on the back of the card. The CVV is often printed on top of the fragile signature strip, and is never encoded into the data stored on the magnetic stripe. The idea is that the CVV is a basic anti-fraud mechanism for so-called Card Not Present transactions, which is why you are often asked for it when paying over the phone or online. A skim of your card’s magstripe, or an imprint from an old-fashioned zip-zap machine (they still exist!), doesn’t capture the CVV. If crooks get hold of a traditional credit card dump, consisting only of data that can automatically be acquired from the card, they can’t easily use your card online. The crooks can, however, create cloned cards, using counterfeit blanks bought online, at least in countries that still widely accept unchipped cards, and go on a spending spree. In this case, they often recruit money mules who are already in trouble with the law, for example because they’re illegal visa overstayers who can’t get jobs and are desperate for undocumented income. If the dishonest purchasers are caught, they’re in double trouble, and they can simply be hung out to dry by the crooks, left to face prosecution, prison and deportation in no particular order. (Basic vigilance during the sales process and at the checkout can often rumble this sort of fraud.) But with a skimmed card and the CVV, the crooks can use stolen cards online, without ever entering a real shop, standing in front of a checkout person, being asked to show photo ID, or facing up to a suspicious security guard. Securing the CVV Of course, the ongoing usefulness of your CVV depends very heavily on it never, ever being stored permanently anywhere except the printed digits on your card. Once a transaction goes through, the CVV should be discarded and not left behind in memory, saved on disk, written into a logfile, or otherwise helpfully remembered until next time. In fact, in this so-called “Bluesnap” breach, it looks as though the payment processor didn’t intend to save the CVVs, but nevertheless managed to dump them into the stolen database as part of a debug log. According to well-known breach-tracker Troy Hunt, the dumped database has fields such as first_name, last_name, expire_year and other bad-enough-on-their-own data items. But it also has a giant field at the end of every record called xml_debug, in which all sorts of additional data, including the CVV, is included as a blob of XML. The XML includes a subfield called card-number that is rendered as TAKEN OFF FOR SECURITY REASONS, even though it’s technically lawful to store card numbers (though they must be protected when saved). Ironically, however, the redacted card number is almost immediately followed by another subfield called security-code, where the never-to-be-stored-at-all CVV code can be found in clear text. Bluesnap, which gives its name to the file that was dumped, is indeed a payment processing provider, but the company is quoted on Troy Hunt’s site as saying: We were not breached. Immediately following the original discovery, we hired a top Security Consulting firm to run an audit of our environment. They concluded that BlueSnap was not the source of the data loss. What to do? If you request and use CVVs at any time, you MUST NOT store them, so don’t. Don’t write them down on paper, don’t save them to disk, and don’t include them in logs. If you keep debugging logs, review them regularly to make sure you aren’t storing prohibited data by mistake. Don’t allow programmers to add data collection features to production code without a strict approval process, even if their motivation is to do the right thing and fix a known problem. If you record phone calls “for security purposes,” don’t record the parts during which you expect purchasers to read out credit card details aloud. The irony of weakening security under the guise of improving it, by carefully recording prohibited data, should be obvious. Source: Sophos

-

- breaches

- credit card

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

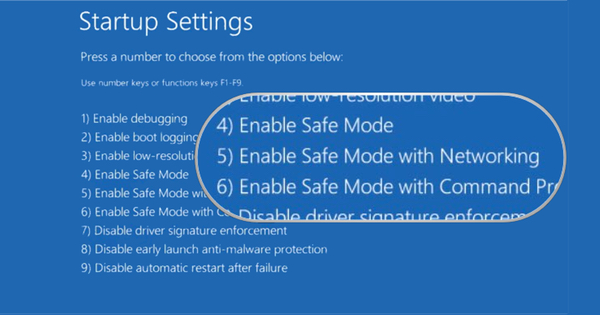

Safe Mode is a great feature for Windows computers in that it allows a user to resolve issues they might not ordinarily be able to address in Normal Mode. That's because Safe Mode runs only software that is critical to the proper functioning of the Windows operating system. But safety isn't equivalent to security. Windows Safe Mode prevents a lot of third-party software that isn't necessary to boot up the PC from running, including anti-virus solutions. Attackers can therefore abuse Safe Mode to launch their exploits, whereas they might be prevented from doing so in Normal Mode. To illustrate that point, researchers at CyberArk Labs have described a method by which attackers could exploit Safe Mode on a PC to execute pass-the-hash attacks and other campaigns. The attack begins with an malicious hacker gaining local admin privileges on at least one machine on the corporate network. It doesn't matter how they do it, but if they had to choose, they might choose to target a particular individual in an organisation with a malicious email. From there, hackers would need to look for vulnerable endpoints where they could reuse stolen login credentials to move laterally throughout the network. That's where Safe Mode comes in. As explained by Doron Naim, a senior security researcher at CyberArk: "Safe Mode, by design, does not boot any software or drivers that are not critical to the operation of Windows. As a result, by remotely forcing a reboot in Safe Mode, attackers inside a compromised system are able to operate freely, as most endpoint defenses are not enabled. And because [Virtual Secure Module] VSM is only enabled in Normal Mode, attackers can also capture credential hashes needed to laterally move through the environment – despite Microsoft’s claims that pass-the-hash risks have been mitigated..." A hacker must do three things to pull off this attack: Remotely configure an infected machine to reboot into Safe Mode. This can be done using BCDEdit. Configure attack tools to run in Safe Mode. A hacker can include a malicious service that runs only in Safe Mode in their initial payload. Alternatively, they can register a malicious COM object to run every time explorer.exe executes. Reboot the machine in Safe Mode. The actor can just wait for the next restart or create a fake "update" window that asks the victim to restart their computer. From there, the attacker can achieve any number of outcomes, including lateral movement or even credential theft. As Naim observes: "If the attacker’s goal is to steal credentials for future use, then the attacker actually wants the user to log on to the system. As the user logs in, the attacker can capture the credentials. In this case, the attacker will likely use the COM object technique to execute code that will change the background, look and feel of Safe Mode – making it appear that the user is still in Normal Mode. As soon as the user enters his or her credentials, a second “update” window can prompt the user to reboot yet again to move the machine back into the actual Normal Mode. Just as mentioned above, this secondary reboot prompt can mimic a legitimate Windows prompt to prevent the user from noticing anything suspicious." Malware in the wild have exhibited that type of one-two update scheme to conceal their activity. That includes some variants of Cerber ransomware. In a test, CyberArk's researchers found that once they modified the registry keys in Minimal Safe Mode, they were able to run Mimikatz and steal credentials without a security solution removing the program from the machine. Given the risks associated with that type of attack, Naim recommends that sysadmins restrict administrator privileges, employ security tools that work in Safe Mode, and overall monitor who's going into Safe Mode and what they're doing once they're there. That's all they can do... Microsoft has refused to fix the issue as they say someone must already compromise a machine to initiate this sequence. Interesting. In my opinion, a security hole is a security hole, including if it serves as a secondary attack vector. Source: Graham Cluley

-

-

The Florida woman who was shocked to receive a $9,100 bill from Verizon Wireless for data she says she couldn’t possibly have used is off the hook, as the company has decided not to make her pay up. To recap: A Tampa woman who never goes over her monthly 4 GB data allotment was suddenly hit with a bill for $8,535 because Verizon said she used 569 GB. Tack on the $600 fee she’d have to pay to leave the company for T-Mobile, and her total bill was $9,135. She told The Plain Dealer that a company representative called her late on Wednesday afternoon, the same day the Cleveland newspaper and The Tampa Bay Times published stories about her situation. She says the representative didn’t offer an apology, but instead just said: “We’re going to resolve all of the data overages,” without explaining why her bill spiked so dramatically, or why the company had a change of heart. Verizon didn’t respond to the Plain Dealer’s requests for comments, but did tell The Times, “We’ve talked with the customer who reported a $9,000 monthly wireless bill and resolved it to her satisfaction.” Verizon did want the woman to pay the $600 cancellation fee, and she’s agreed to do so. But the $20 she paid when Verizon said she needed more data? She’s not paying for that. The company agreed, and asked if she was ready to pay off the rest of the bill right then. “I said, ‘No. I want to see something in writing,'” she told the Plain Dealer. “I want to make sure everything is taken off before I pay anything.” Verizon agrees to drop Florida mother’s $9,100 cellphone bill [The Plain Dealer] This is the story of the Wesley Chapel woman whose Verizon cellphone bill shot from $118 to $9,153 [Tampa Bay Times]

- 2 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- data allotment

- overages

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Imagine the damage that could be caused if a criminal was able to infect an Android smartphone remotely just by sending it a message, knowing nothing more than the device’s phone number or email address. It’s easy to imagine how governments, intelligence agencies and organised criminal gangs would be prepared to pay a large amount of money for exclusive details of just such a critical flaw, using it to steal and spy on unsuspecting targets. With that in mind, Google has announced a hacking contest offering a $200,000 first prize to vulnerability hunters around the world if they can find a way to remotely hack an Android device knowing nothing more than its phone number or email address. Although $200,000 is being offered to the first winning entry, there are other prizes on offer (a second prize of $100,000, a third prize of at least $50,000 offered to additional winning entries. (Bad news if you’re a bug hunting ninja – Google says you can only win one prize) As exploit researcher Natalie Silvanovich explains, the competition hopes to improve the security of Android: “There are often rumours of remote Android exploits, but it’s fairly rare to see one in action. We’re hoping this contest will improve the public body of knowledge on these types of exploits. Hopefully this will teach us what components these issues can exist in, how security mitigations are bypassed and other information that could help protect against these types of bugs.” That is, of course, all marvellous. But it’s not all good news. Because even if seriously vulnerabilities like those described in the competition are discovered and patched, that is no guarantee that the vast majority of Android users will be protected against them. The availability of Android security updates depends upon the assistance and goodwill of three parties: Google itself, your device’s manufacturer and your phone carrier. Even if you are desperate to upgrade the version of Android on your device to take advantage of the latest security patches, that decision is taken out of your hands and you can easily find yourself stranded on an out-of-date device without an easy update path. I know it’s not always technically possible to deliver the latest and greatest version of Android to older devices, but more companies need to follow the example set by Google and Samsung in creating an easier path for updates to fix critical, newly-found vulnerabilities. Google’s competition will run for six months, with exploits that successfully target Android Nougat on Google Nexus 5X and 6P devices eligible for entry. Google has detailed the full rules of the competition, and how to enter, here. Source: hot for security

-

That's weird. I wonder if that has something to do with it?

-

They should show up in the Inbox. I don't have any idea why they don't.

-

Director of the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) James Comey puts tape over his webcam and he wants you to do it too. Speaking at the recent Center for Strategic and International Studies conference on Wednesday, Comey likened covering your cam to locking your car and the door to your home. Comey has spent 2016 generating headlines. In February and March he squared up to Apple who, spying a very slippery slope, declined to help the FBI crack an iPhone used by one of the perpetrators of a mass shooting in San Bernadino, California. In June he called time on the FBI’s investigation into Hilary Clinton’s personal email server with an incendiary press release that absolved Clinton of “intentional misconduct” but accused her and her team of being “extremely careless”. April wasn’t exactly quiet either. The man who wants a backdoor to your iPhone faced a tweetnami of snark and schadenfreude for revealing he used a “warrant-proof anti lawful surveillance” device (he puts tape over his webcam.) Comey admits to being “much mocked” for the admission, made during a question and answer session with students from Kenyon College in Ohio, but on Wednesday he doubled-down. It was, he said, something you should be doing too: There’s some sensible things you should be doing, and that’s one of them … You do that so that people who don’t have authority don’t look at you. I think that’s a good thing. Another great surveiller apparently agrees. In June Mark Zuckerburg posted a photo of himself that revealed he, too, is taking steps to protect himself from cam-hacking malware. Putting something, like a cover or tape, over your webcam might seem a little close to wearing a tinfoil hat but it’s actually a good idea. Hackers who can find a way in to your computer can use their access to install malicious RAT (Remote Access Trojan) software that gives them unfettered access to what you type on the keyboard, say near the microphone or do in front of the camera. Covering your webcam isn’t a substitute for keeping your systems patched and running effective anti-virus but, if you’re doing both those things, it’s another layer of defence in depth that’s worth considering and easy to apply. And you don’t have to use tape. Source: Sophos

-

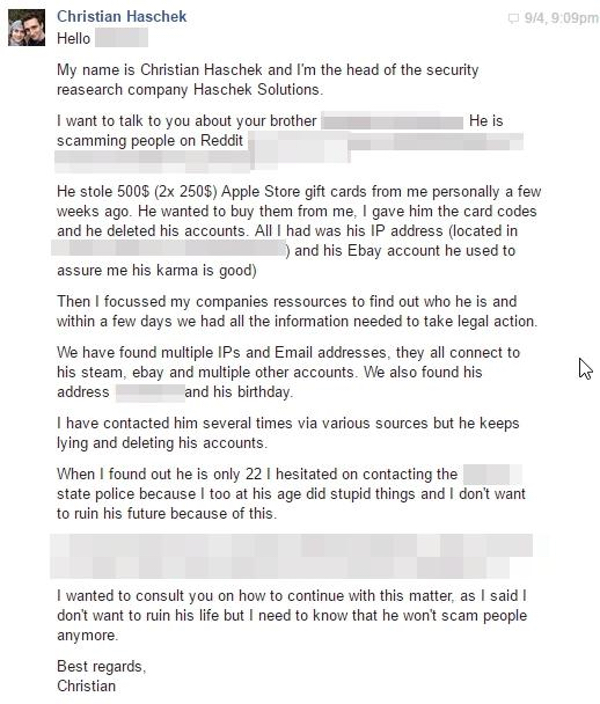

Using the same username across the web? That may have its drawbacks… Some scammers think the chances of the police ever catching them are low, but there's one thing they are afraid of: their mum. Security researcher Christian Haschek tells the story of how he tried to sell some Apple gift cards online that he won in a competition, but ended up handing over the gift card codes... and not receiving any money in return. Although the scammer tried to fade away, Haschek knew the usernames that the gift card robber had used on eBay and Reddit. That eBay nickname had also been used on a freelance job search site, providing his first name, the first letter of his surname, and confirmations of his city. The information collected so far brought Haschek to a likely Facebook profile belonging to the scammer - but its locked-down privacy settings prevented much further information being extracted. No matter, one of the scammer's friends was a lot more lax with their Facebook privacy settings, and Haschek was able to trawl through four years' worth of old posts - eventually revealing the scammer's full name. So, now what? Well, Haschek found the scammer's older brother and mother online, and sent them this message: Check out Christian Haschek's blog post to find out what happened next. :) So, what can we learn from this? Well, when you reuse usernames across the web you're helping others pull the strands of information together to weave a picture of who you are, where you might live, and what your interests might be. Furthermore, take Facebook privacy seriously and be careful what you post and how you share it. Sadly it's not enough for you to be careful with your online privacy - you also need your friends, family and colleagues to be just as wise to the risks of sharing too much information. Finally, take care when you sell things online. Source: Graham Cluley

-

I guess that I am kind of stuck with AdBlock Plus and Ad-Muncher because I use Internet Explorer.

- 6 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- ad-tech

- adblock plus

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

-

On Tuesday, adblocking company Adblock Plus launched a new platform… to sell ads. The company announced the controversial move on its blog, saying that it was: … launching the beta version of a fully functional ad-tech platform that will make whitelisting faster and easier. So, what exactly does that mean? The Acceptable Ads platform As part of the company’s Acceptable Ads initiative, advertisers and publishers who have agreed to make ads that abide by a number of specific criteria can be ‘whitelisted’. The criteria demands that ads don’t disrupt a user’s natural reading flow, are easily identified as ads and conform to specific maximum sizes. By default, users will see ads that are whitelisted but they can also disable their Acceptable Ads option to block all ads completely. The Acceptable Ads Platform, as it is known, also lets publishers and bloggers select pre-whitelisted ads to use on their sites. AdBlock Plus users will see the Acceptable Ads-approved ad whilst everyone else will see whatever ad would have been running there anyway (unless they’re using a different adblocker!) No ads at all Underpinning the move is an assumption, backed up by AdBlock Plus research, that people block ads because they don’t want to see ‘intrusive’ ads, rather because they don’t want to see any ads ever. In fact, Adblock Plus seems to have almost forgotten this group of users. The Guardian shares a quote from Adblock Plus co-founder Till Faider that clearly neglects them: There are two ecosystems of online consumers out there right now: the one composed of people who block intrusive ads and the other where people do not. The Acceptable Ads Platform lets publishers reach the former group without changing anything about how they’re reaching the latter. This new platform may well alienate them and send them fleeing elsewhere. As John Koetsier writing for Forbes puts it: AdBlock Plus, whose users adopted the technology to avoid advertising altogether, may well decide to vote with their feet and leave for greener pastures, like other adblocking technologies. A form of extortion? In its analysis of this controversial move, Koetsier describes the launch of this platform as a “fox guarding the hen house”. Jacob Kastrenakes writes in the Verge: In setting up its own marketplace, Adblock Plus continues to position itself as a gatekeeper charging a toll to get through a gate of its own making. And a toll there clearly is going by the figures published in The Guardian: Publishers will get to keep 80% of the advertising revenue from ads sold through the marketplace, and the rest will be divided between Adblock Plus and other partners. Which means that whilst it rolls the dice with its users AdBlock Plus also risks alienating publishers too. Even before this move Advertising Bureau CEO Randall Rothenberg had already described AdBlock Plus as an “extortion-based business and hurts publishers”: AdBlock Plus is in the business of taking the revenue that these publishers should earn and then divert[ing] it into their own pockets. Understanding user needs To me, the success of this platform hinges on Adblock Plus’ understanding of its user base. If, as the company believes, the majority of its users feel that all ads are not equally annoying and that some are acceptable, then it may be onto a winner – if and only if the ads it whitelists really are what its user base wants to see. If, on the other hand, the majority of users don’t want to see any ads at all or if Adblock Plus loses touch with what ads its users want (and this is bound to evolve over time), then this business model could be doomed. It’s a brazen move. Only time will tell if it pays off… Source: Sophos

- 6 replies

-

- ad-tech

- adblock plus

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with: